Background

Allocation bias may result if investigators know or predict which intervention the next eligible participant is supposed to receive. This knowledge may influence the way investigators approach potentially eligible participants and how they are assigned to the different groups, thereby selecting participants with good prognoses (i.e. anticipated good outcomes and treatment responses) into one group more than another.

In a trial of different blood pressure medications the use of sealed envelopes to conceal the allocation schedule resulted in imbalances in baseline blood pressure between the treatment and control groups. In turned out that participants in the control group already had lower blood pressures compared to participants in the treatment group at the outset. The observed imbalance could have arisen if the investigator opened the envelopes before allocating participants to groups.

Example

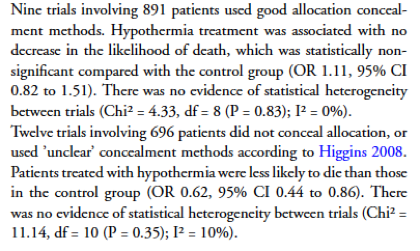

In the nine trials using good allocation concealment, there was no detected effect of hypothermia treatment on death, whereas in the trials that did not conceal allocation there was a 38% reduction in the risk of death. Hypothermia for traumatic head injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009.

Impact

There is evidence that over 80% of trials have unclear allocation concealment. Trials in which allocation was inadequately concealed reported estimates that were between 7% and 40% larger than effects in trials in which allocation was adequately concealed, although the size and direction of the effect were not predictable. A simulation of trials showed that, due to knowledge of previous allocations, as many as 1 in 5 trials could conclude that there was a difference when in fact there was not.

Trials with inadequate allocation concealment yield estimates that are up to 40% larger than those that do not. Empirical evidence of bias. JAMA. 1995.

Preventive steps

Some standard methods of ensuring concealment of group allocation prior to allocation include sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE); sequentially numbered containers; pharmacy controlled allocation; and central allocation.

When trialists do more to show that group allocation (prior to allocation) was concealed, this permits more confidence that allocation bias has not affected the study’s results. For example, an audit trail can be recorded for sequentially numbered envelopes; sequentially numbered containers should look identical to each other from the outside; study staff should have correct training for maintaining allocation concealment; the block sizes for randomization should not be known; and all these features of the trial should be reported in the trial publications.

Where cluster randomisation or minimisation are used in the allocation to treatment or control groups, it may not be possible to prevent future allocations being predictable and thus concealment might not be adequate. In such cases, pre-defined statistical adjustments (e.g. covariate analysis) can be considered and should be reported in trial publications.

Researchers should try to understand the reasons for allocation concealment and the problems that can arise if a robust trial protocol including allocation concealment is not followed. Allocation concealment procedures should also be specified in a trial’s protocol, and reported in detail in any publication of the trial’s results.